Would An Independent West Papua Be A Failing State?

David Adam Stott

“Where it cuts across the island of New Guinea, the 141st

meridian east remains one of colonial cartography's more arbitrary yet

effective of boundaries.”1

On July 9, 2011 another irrational colonial border that demarcated

Sudan was consigned to history when South Sudan achieved independence.

In the process an often seemingly irrevocable principle of

decolonisation, that boundaries inherited from colonial entities should

remain sacrosanct, has been challenged once again. Indeed, a cautious

trend in international relations has been to support greater

self-determination for ‘nations’ without awarding full statehood. Yet

Kosovo is another state whose recent independence has been recognised by

most major players in the international community.2 In West

Papua’s case, the territory’s small but growing elite had been preparing

for independence from the Netherlands in the late 1950s and early

1960s, and Dutch plans envisaged full independence by 1970. However, in

1962 Cold War realpolitik intervened and the United States engineered a

transfer of sovereignty to Indonesia under the auspices of the United

Nations. To Indonesian nationalists their revolution became complete

since West New Guinea had previously been part of the larger colonial

unit of the Netherlands East Indies, which had realised its independence

as Indonesia in 1949. In West New Guinea, most Papuans felt betrayed by

the international community and have been campaigning for a proper

referendum on independence ever since.

Jakarta has staunchly resisted any discussion of West Papua’s status

outside of the Unitary Republic of Indonesia. However, in February 1999

Papuan civil society representatives convened in Jakarta for

unprecedented talks with President Habibie, Suharto’s successor who was

eager to demonstrate his reformist credentials. Habibie’s own successor

Abdurrahman Wahid initially attempted a policy of tentative engagement

with Papuan civil society, which included sponsoring the Papuan Congress

of May 2000. This so-called ‘Papuan Spring’ of 1999-2000 marked the

zenith of pan-Papuan organising and solidarity, prompting speculation

that West Papua might follow East Timor in conducting a referendum over

its status. During this period Papuan nationalists were also able to fly

their Morning Star flag for the first time without fear of long jail

terms or violent reprisals. However, as hardliners in the Indonesian

military consolidated power after a period of relative weakness, the

flowers of the Papuan Spring withered and Wahid was removed from office

in July 2001.3

|

Papuan girl at an independence rally in Wamena, August 2011. Photo by Alexander Pototskiy

|

In response to the Papuan Spring, the Indonesian authorities have

pursued a dual strategy — a repressive security approach that also

characterised the Suharto years (1966-1998) and co-option of local

elites through the 2001 Special Autonomy Law, which has been used to

promote greater Papuan participation in local administration. The

security approach has combined increasing troop numbers with greater

surveillance of civil society, and since mid-2000 the state has again

responded to flag-raising ceremonies with violence and long prison

terms. In a symbolic act, the Indonesian military’s special forces also

killed Papuan Congress chairman Theys Eluay in November 2001. Meanwhile,

the Special Autonomy Law, on paper a much more comprehensive devolution

of authority than most other provinces gained under Indonesia’s

nationwide regional autonomy legislation of 1999, was designed to

assuage Papuan demands for independence.4 However, whilst the

territory does receive the biggest per capita allocation of central

government development funds in Indonesia, Jakarta does not trust

indigenous Papuan officials enough to properly implement Special

Autonomy and has therefore severely curtailed much of the promised

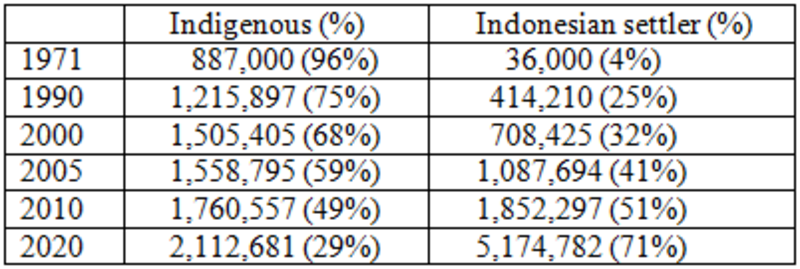

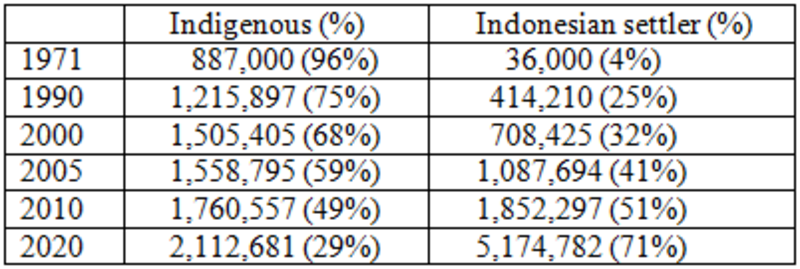

autonomy.5 Its halting implementation has also been accompanied by increasing numbers of Indonesian migrants settling in West Papua.

So far, this dual strategy of dividing Papuan civil society and

increasing the costs of Papuan resistance has appeared effective since

the momentum generated during the Papuan Spring has not been sustained.

Nevertheless, the frequent demonstrations across the territory

protesting the failures of Special Autonomy and demanding a referendum

have taken on a greater urgency since Indonesian migrants now constitute

more than half of West Papua’s population. However, if allowed to vote

in a referendum it is probable that many of these settlers would view

continuing integration with Indonesia as more in their interest. This

raises the question of whether they could or should be excluded from

participating in any vote on West Papua’s status. At the time of East

Timor’s referendum in 1999, Indonesian migrants constituted around 10%

of its population and were excluded from the voter registration process.6 For

Papuan nationalists, the demographic situation is therefore much more

perilous, and it has also been argued that an independent West Papua is

unviable.7 This paper will attempt to analyse what kind of

independent state West Papua might become if the territory were to

follow Timor-Leste and South Sudan into statehood. Would it become

another so-called ‘failing state’, like its closest neighbours Papua New

Guinea (PNG), Timor-Leste and the Solomon Islands? By examining some of

the difficulties affecting West Papua’s neighbours post-independence

this paper will introduce some of the main challenges an independent

West Papua could likely face. In conclusion it will examine the

prospects for a better future for ordinary Papuans, whether through

independence or genuine autonomy within Indonesia.

Melanesia or Asia?

The division of New Guinea between two states, indeed between two

continents, can be traced back to 1828 when the Dutch proclaimed their

territorial possessions ended at the 141st meridian east, roughly

halfway across the large island. During the scramble for empire that

also decided the colonial demarcations of Africa, New Guinea’s eastern

half was to be administered by German, British and, subsequently

Australia colonial governments, before gaining independence in 1975 as

Papua New Guinea. However, the western half of New Guinea remains a

colony, having being forced in 1962-3 to swap Dutch colonialism for a

much more pernicious, militarised Indonesian form. As such, this

accident of colonial cartography has proved remarkably durable, and

through Indonesian control officially demarcates the border between Asia

and Oceania, with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to

its west and the Pacific Islands Forum to the east.

Indigenous Papuans are a Melanesian people in common with Pacific

neighbours PNG, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and Fiji, and

are thus racially and ethnically distinct from the vast majority of the

Indonesian population. With the exception of partly Polynesian

contemporary Fiji, Melanesian countries are characterised by an

extremely large number of indigenous ethnic groups due to geographic

factors that have encouraged massive linguistic diversity and clan-based

ethnic identities. In the case of New Guinea such factors include

mountainous terrain, dense rainforests, steep valleys, impenetrable

marshland and large distances, which have combined to create isolated

communities speaking different languages and developing different

cultures. Indeed, New Guinea is home to almost 1000 indigenous

languages, with a reported 267 on the Indonesian side, representing

around one-sixth of the world’s ethnicities.8 In PNG, Solomon

Islands and Vanuatu these micro-polities are so numerous that none are

able to impose hegemony over others at national level. Whilst these

micro-polities have often fought each other, ethnic conflict is usually

restricted to a local level, unlike in sub-Saharan Africa where it has

also existed at a national level, most notoriously Rwanda in 1994. Thus

creating small, relatively heterogeneous single-member electoral

districts or constituencies has been viewed as a potential strategy to

minimise ethnic tensions at a local level in PNG, Solomon Islands and

Vanuatu.9

Whilst such extreme ethnic fragmentation is rare outside of

Melanesia, the presence of large numbers of Indonesian settlers makes

the situation in West Papua uniquely complicated. Indeed, Indonesian

migrants in West Papua themselves constitute a plethora of ethnic

groups, representing the archipelago’s ethnic diversity. Most Indonesian

settlers in West Papua come from Maluku, Sulawesi or Java. Despite the

diversity of both native and migrant groups, both view the distinct

differences in skin tone, hair type and even diet as symptomatic of

intrinsic differences that override any other ethnic categorisation.10

The first wave of Indonesian migrants in the colonial era were

Christian teachers, officials and professionals from the nearby

territories of Maluku and North Sulawesi, brought in by the Dutch

administration to help run the territory prior to World War II.11 After

1945, the Dutch forced the departure of many of these functionaries to

prevent the spread of Indonesian nationalism but around 14,000 of them

were still living in Dutch New Guinea in 1959, with around 8,000 being

from the neighbouring Maluku archipelago.12 Since many of

these middle-ranking officials had served the brutal Japanese occupying

regime, the seeds of Papuan resentment towards Indonesian settlers had

already been sown.13 The United Nations-administered

transition period of October 1962-May 1963 effectively began the

Indonesian takeover, and resulted in an influx of Indonesian civil

servants and security personnel, mostly Muslims from Java. This too

caused resentment since they replaced Papuans who had been trained under

the Dutch for self-governance. In February 1966 a hundred Javanese

families set sail for the territory, thus slowly beginning the West

Papua chapter of Indonesia’s nationwide transmigration programme, which

subsidised families to move from overcrowded regions to less-populated

parts of the archipelago.14 Between 1969 and 1989, the

programme moved some 730,000 families from Java, Madura and Bali to

Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku and West Papua.15

The transmigration policy reached its zenith in the 1980s, and the

number of ‘official transmigrants’ in West Papua is now dwarfed by

‘spontaneous transmigrants’ who migrated internally with little or no

government help. This constitutes two separate patterns of migration

since many of the largely Muslim Javanese official transmigrants were

originally settled in rural areas where few other migrants ventured. The

self-funded migrants originate mainly from eastern Indonesia, mostly

Muslims and Christians from Sulawesi and Maluku who usually settle in

urban areas along the coast.16 It is these self-funded

migrants whose numbers are rising vertiginously. In addition to

spontaneous economic migration, other drivers of contemporary Indonesian

migration into West Papua are the expansion of the bureaucracy that

accompanies the national decentralisation process and large-scale

agricultural ventures such as palm oil plantations and the proposed

Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate. Plans to convert even more

land to palm oil and other plantation crops will likely increase the

rate of migrant population growth. By contrast, the indigenous Papuan

population is unlikely to grow much faster in light of poor healthcare

in rural areas and much higher rates of HIV among indigenous Papuans

than Indonesian migrants.

Indigenous and Indonesian settler population in West Papua17

One particular difficulty that would immediately confront policy

makers in an independent West Papua is the fact that the territory has

become divided into two realms - of the (mostly coastal) towns and

cities, where migrants constitute the majority and dominate all

commercial activity; and the rural interior, which is overwhelmingly

Papuan, employed in subsistence farming and often only loosely connected

to the modern, cash and international economy. For example, data from

the 2000 census shows that in Mimika regency, where the huge Freeport

gold and copper mine operates, those born outside of the regency made up

some 57% of the population and in Jayapura regency, the territory’s

biggest urban centre, they constituted 58%.18 Whilst the

towns and cities are relatively prosperous by Indonesian standards, the

countryside is populated by an underclass of indigenous tribes who

suffer the worst living standards in Indonesia. Since the coastal areas

contain most of West Papua’s industries and work opportunities in the

formal economy, they also attract better-educated Indonesian settlers

who invariably secure the best private sector positions. For instance,

it has been estimated that these migrants possess more than 90% of all

trading jobs in the territory, and they also dominate the manufacturing

sector.19

Papuan rural to urban migration in search of employment actually

predates the Indonesian takeover since it began during the Allied war

effort and increased with the Dutch expansion of government after their

return in September 1945. Wage labour for the war effort and

subsequently the Dutch colonial administration was the major form of

employment for almost twenty years but such opportunities became scarcer

for indigenous Papuans after the Indonesian takeover, forcing many back

into a subsistence lifestyle. Migrant domination of the coastal towns

and cities continues to crowd out indigenous Papuan migration to urban

areas, thus reducing their employment opportunities in the formal, cash

economy. Indeed, as migrants continue to arrive they consolidate

existing ethnic networks, which are vital for gaining choice employment

in Indonesia. Given the relative paucity of the indigenous business

class, such ethnic networks work against Papuan job hunters, with the

result that Papuans continue to work mainly in subsistence farming.

Exacerbating this divide, migrants have also achieved greater success in

commercial agriculture, allowing them to take control of local markets.

This reality is already a significant issue for both provincial

administrations to handle, and has prompted calls for positive

discrimination for indigenous Papuans to better compete in the job

market. How an independent West Papua deals with this problem would

likely have a substantial bearing on the stability and viability of the

nascent nation state.

Failed States

In 2007 Chauvet, Collier and Hoeffler estimated the total cost of

failing states at around US$276 billion annually in lost GDP, with

Pacific island nations accounting for US$36 billion of that.20 The

Failed States Index, which perhaps should be described as the failing

states index, defines a failed state as “one in which the government

does not have effective control of its territory, is not perceived as

legitimate by a significant portion of its population, does not provide

domestic security or basic public services to its citizens, and lacks a

monopoly on the use of force.”21 In the 2011 Index some 177

sovereign states are ranked on their vulnerability to collapse according

to 12 indicators, among them conflict, corruption, demographic

pressures, poverty and inequality. The rankings are headed by Somalia

and dominated by countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Timor-Leste was

perceived to be the most vulnerable state among West Papua’s neighbours,

although its 23rd place ranking reflects an improvement in its domestic

security situation since 2008. The Solomon Islands was ranked 49, PNG

54, Indonesia 64 and Fiji 68.22

Whilst the spillover effects of state failure to their neighbours are

reduced since Pacific countries are islands, Chauvet et al (2007) warn

that, “The cost of failure might be higher than average in small islands

because they are atypically highly exposed to the global economy”. This

is largely due to the fact that, “Both capital and labour are likely to

be highly mobile internationally in small islands.”23 The

implication is that the residents of the country itself shoulder most

costs of state failure in the Pacific, in contrast to other regions

where the spillover effects to neighbours are much higher. The same

research calculated that over a 20-year period the total cost of such

state failure in PNG amounted to some US$33.5 billion, or around US$1.7

billion in lost GDP per annum, whilst in the smaller Solomon Islands it

reached US$2.2 billion, equivalent to US$0.1 billion per year.24 If

correct, this hypothesis suggests that state failure could be

particularly damaging to an independent West Papua trying to find its

feet.

Failed states are usually characterised by high political

instability; rampant corruption; dysfunctional economies; collapse of

government services; breakdown of law and order; internal conflicts; and

loss of state authority and legitimacy. Such state paralysis allows

local and traditional leaders to displace the state’s power in their

respective areas, and the state becomes effectively unified in name

only. In Melanesia’s case a youth bulge also further threatens

stability, and PNG and the Solomon Islands are the states most closely

associated with state failure within the whole Pacific islands region

which also encompasses Polynesia and Micronesia. In both countries high

crime rates, extensive political corruption and rampant tribalism are

becoming increasingly threatening. By analysing the present situation in

West Papua this section will consider whether some of the pressing

issues gripping its neighbours would likely affect an independent West

Papua too.

Political Instability

“Melanesia and East Timor are now widely perceived in official and

academic circles as an ‘arc of instability’ within which economic

development has also largely stalled.”25 Whilst only Fiji has

suffered military takeovers, political instability has characterised

Melanesia since independence. Across the region unrepresentative elites

often manage to seize control of the state and use their positions for

self-enrichment and empowerment of their own narrow constituencies,

usually confined to members of their own clans or language groups. The

pre-eminence of these so-called ‘Big Men’ is highly entrenched and feeds

a situation in which locals see themselves as “followers of the state”,

that is “personified as a big man . . . bound by . . . reciprocity to

look after and redistribute resources to his followers”.26 The

legitimacy of such big men and their administrations derives both from

their ability to sustain patronage networks and from international

recognition and assistance. As has been the case across both Indonesia

and Melanesia, diverted development funds and revenues from commodity

exports enriches politicians, their cronies and public servants,

engendering mistrust of the authorities, hampering development efforts,

fostering rising levels of crime, and even encouraging internal

rebellions.27

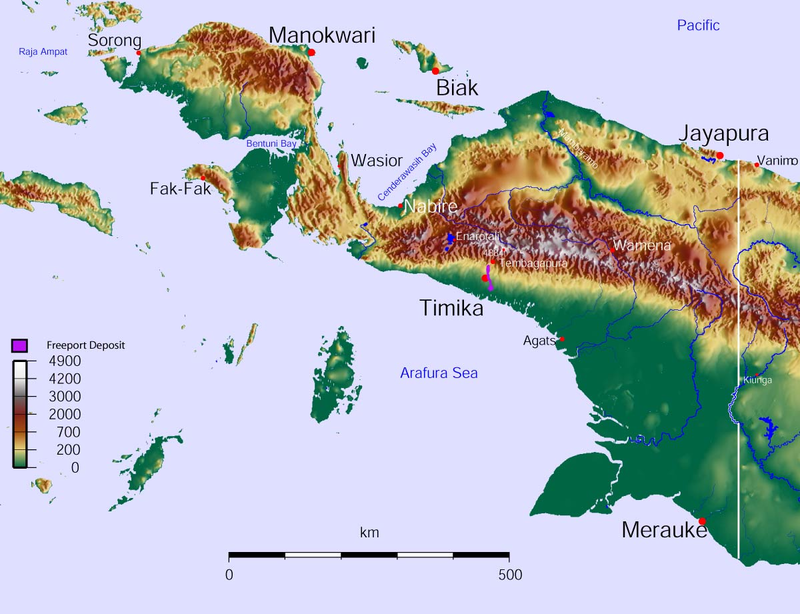

|

Topographical map of West Papua

|

The extent to which such a patronage-based style of politics has

contributed significantly to state weakness and political instability

across Melanesia and the Pacific is particularly visible during

elections. A familiar pattern in elections in PNG, for instance, is an

unwieldy number of candidates and parties competing against each other

in which over 50% of sitting candidates are not returned. Many new

members win their seats with under 10% of the vote and consequently

cannot or will not represent the remaining 90%. Intense bargaining often

ensues after the votes are tallied, with the many independent

candidates trading their votes for handouts to their supporters.

Political parties in PNG, and in other Melanesian states, are usually

centred on an individual leader rather than being ideologically based.

Thus, political parties frequently splinter in light of the competing

interests of their leaders, and it could be many years before

issues-based politics become entrenched across the region. The

inevitable outcome is a fractious coalition government fused together

only by corruption and bribery in the absence of party loyalties and

awareness of the public good. Ironically, disillusionment with a

fragmented national parliament further fuels instability since electors

increasingly vote for smaller political parties or local independent

candidates instead of the major national parties. As a result, the

failure of leadership across Melanesia to act in the national interest

is seemingly putting the systems of democracy under threat, especially

in light of the region’s rapidly growing, increasingly urbanised young

population.

The Westminster system of parliamentary democracy as practiced in

Melanesia has not proved able to hold elected politicians to account

partly because the electorate seems to have little concept of how the

system is meant to operate. Furthermore, many of the MPs that get

elected have no genuine understanding of how the Westminster system

should operate. Instead, many only care about getting in to parliament,

securing a government post that guarantees all the perks and privileges,

and then clinging onto power. A politician in Melanesia needs to pay

back those who voted for him, and a government position is usually the

only means to do so. The inevitable result is that politicians spend

their entire term in parliament maneuvering to get into government by

any means necessary, leading to frequent motions of no confidence in the

sitting government by those attempting to form the next government. As a

consequence, the whole basis of democracy in Melanesia appears

inherently unstable, and illustrates the problematic nature of grafting

liberal democratic political systems onto traditional authoritarian

arrangements of hierarchy and leadership.

Indeed, democracy appears to be in crisis in all of West Papua’s

closest neighbours. Whilst PNG, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu are all

formally constituted on the Westminster system of parliamentary

democracy, each suffers regular constitutional crises and parliamentary

votes of no confidence. For instance, PNG’s acting prime minister is

currently facing a Supreme Court challenge over his, allegedly

unconstitutional, appointment in December 2010, whilst his predecessor

had been trying to install a new governor-general, an appointment beyond

the remit of the prime minister. The widespread fraud and violence that

overshadowed PNG’s general elections in 2002 and 2007 also suggests

that democracy is under siege. Meanwhile, the Solomon Islands has had 15

governments since independence in 1978, the vast majority of which have

been unstable coalitions in a persistent state of flux and under

constant threat of no-confidence votes. Indeed, the very first act of

the newly appointed opposition leader in April 2011, himself a former

prime minister, was to lodge a motion of no confidence in the sitting

government. In Vanuatu the government was toppled in a similar

no-confidence vote at the end of 2010, whilst Fiji was formerly a

democracy but a military coup in 1987 ushered in alternating periods of

military rule and parliamentary democracy. The most recent coup of

December 2006 re-established military control and elections scheduled

for March 2009 have been postponed to September 2014 at the earliest.

East Timor also has had a difficult transition to independence.

Violent clashes flared in 2006 when approximately 600 soldiers,

constituting some 40% of the armed forces, were dismissed after

protesting alleged discrimination against troops from the west of the

country. This necessitated the deployment of peacekeeping forces from

Australia, Malaysia, Portugal and New Zealand to quell the violence and

looting in the capital Dili. Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri was forced to

resign and other members of the political elite were implicated in the

troubles. In February 2008 rebel soldiers broke into the homes of

President José Ramos-Horta and Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, resulting

in a serious gunshot injury to Ramos-Horta and the fatal shooting of

rebel leader Alfredo Reinado. Gusmão managed to escape from his home

prior to the rebels’ arrival but his car was peppered by gunshots on its

way to Dili. Whilst political tensions have gradually subsided since

then polarisation ensures the nascent state remains fragile.

Given that none of its neighbours have enjoyed political stability

since independence, it would be a challenge for an independent West

Papua to avoid similar problems, especially since it is currently

suffering from other symptoms that characterise failing states in the

region. A foretaste of instability might be glimpsed in the controversy

surrounding the MRP (Majelis Rakyat Papua or Papuan People’s Assembly), a

body established under Special Autonomy to be staffed entirely with

indigenous Papuans and to represent Papuan cultural interests. Whilst

the body is not equivalent to a second chamber of the provincial

parliament, it does have a role in the legislative process and in theory

should possess significant political authority. However, elections to

the MPR have been dogged by allegations of irregularities, most recently

in February 2011 when Papuan civil society complained about a lack of

transparency in the vote counting process. The provincial parliament and

three Protestant churches were among the dissident voices expressing

their disapproval of the MRP, whose membership and leadership have also

been subjected to interference from the central government. For example,

Jakarta rejected the recent re-election to the MRP of Agus Alue Alua

and Hanna Hikoyobi, the body’s chair and vice chair for the 2005-2010

period respectively, amid accusations that the pair had been using the

MRP to promote Papuan independence. Moreover, the history of the Organisasi Papua Merdeka

(OPM, or Free Papua Movement), the territory’s main armed resistance

movement since 1965, has been riddled with internal ethnic rivalries

that have compromised the group’s effectiveness.28

Corruption

In addition to political instability, corruption is also endemic

throughout Melanesia, particularly in PNG and Solomon Islands but also

to a lesser extent in Vanuatu and Fiji. Indonesia’s reputation for

corruption is well founded too, with many observers arguing that it has

actually worsened and become more diffuse since Suharto’s fall in 1998.29 Transparency

International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2010

ranked Indonesia and the Solomon Islands joint 110th worst out of 178

countries for “the degree to which corruption is perceived to exist

among public officials and politicians”.30 Vanuatu was ranked 73 and PNG 154.31 PNG’s

Public Accounts Committee found in February 2010 that only five of some

1000 government departments, agencies, provincial governments and

statutory organisations it investigated had satisfied the Public

Accounts Management Act to properly account for government funds.

Nonetheless, Port Moresby has shown little inclination to seriously

prosecute corruption cases, strengthening the perception that nepotism

and cronyism are becoming increasingly entrenched. Whilst PNG probably

deserves its low ranking, one weakness of the CPI is that it does not

account for local variations within countries, as anecdotal evidence

suggests corruption varies significantly among the cities, districts and

provinces of many states. The CPI also fails to take into account the

foreign drivers of corruption, which characterise resource extraction

schemes in particular.

Nevertheless, most politicians in Melanesia tend to be motivated by

self-enrichment and localism, an obvious recipe for corruption that is a

strong feature of government in PNG and is being replicated in West

Papua. As part of its policy response to the Papuan spring of 1999-2000,

Jakarta has cultivated an elite of indigenous Papuan politicians and

bureaucrats in order to ameliorate separatist sentiment. The Special

Autonomy Law of 2001 specifies that provincial governors must be

indigenous Papuans and that indigenous Papuans are to be granted

priority appointment as judges and prosecutors. Aside from the position

of governor, Indonesian settlers have controlled the territory’s

bureaucracy, especially at the higher levels. However, under Special

Autonomy the indigenous elite has demanded a greater role in running the

territory, in response to the increasing numbers of Indonesian migrants

dominating the formal private sector. Their vehicle has been the MRP

whose members have also pushed for laws stipulating that local

administration heads and their deputies must be native Papuan. Although

real efforts to employ more Papuans in government service only began in

the late 1990s, as a result of Special Autonomy it was estimated in 2005

that around 35% of the civil service was indigenous Papuan.32 This

contrasts with Dutch efforts that had Papuans comprising around 30% of

the civil service in 1957 and around 75% in September 1962 on the eve of

the Dutch departure.33

Special Autonomy has also dramatically increased the amount of

government money flowing into West Papua. The World Bank has calculated

that transfers from the central government to the territory have risen

over 600% in real terms since 2000, with the result that Indonesia’s

decentralisation policy has mainly served to increase local level

corruption in West Papua.34 In addition to dispersing an

average of US$ 240 million per annum in 2002-2006 under the Special

Autonomy legislation, Jakarta has also provided extra funding for

infrastructure development. This amounted to US$ 72 million 2006 and US$

95 million in 2007.35 Some 60% of Special Autonomy funds are

distributed to the two provincial governments and 40% to local district

governments but these transfers have resulted in little improvement in

health, education and development outcomes in much of the territory.

Despite having been largely marginalised since 1963, it seems that

Papuan bureaucrats and politicians have learned quickly from their

Indonesian colleagues how to enrich themselves via government positions.

Civil servants and local politicians in West Papua have also

benefitted from national level reforms that have created new

administrative divisions throughout Indonesia under a policy known as pemekaran

(literally blossoming or blooming). In West Papua, this process has

again been driven by indigenous elites lobbying for the creation of new

regencies, districts, subdistricts and villages in order to promote clan

interests and gain access to government funds.36 For

instance, local government in the territory had expanded to 38 districts

by 2010 from nine districts in 1998. Such new administrative units

offer customary leaders the opportunity to occupy newly created

positions and to financially benefit from their creation. This has

prompted greater competition for power and influence, fuelling tensions

between ethnic elites particularly in Ayamaru, Biak and Yapen, as well

as between coastal Papuans and those from the highlands interior.37

The territory of West Papua was itself also partitioned in February

2003 into the provinces of Papua and West Papua, with a third province

also proposed. This division of West Papua into three provinces was also

driven by indigenous elite rivalries, and led to violent demonstrations

in which several protesters were killed. Whilst the proposed Central

Irian Jaya province was later shelved, the creation of West Papua

province was allowed to stand as a fait accompli despite the

Constitutional Court ruling that this split violated Papua province’s

Special Autonomy Law. The establishment of West Papua province stemmed

from Papua province’s 1999 gubernatorial elections won by Jaap Solossa.

His defeated opponent was Marine Brigadier General (retired) Abraham

Atururi, who had been one of the three deputy governors under the

previous governor. Whilst both Solossa and Atururi benefitted from Dutch

primary and secondary education and subsequently worked with the

Indonesian authorities after the sovereignty transfer, ethnic

differences characterised their political rivalry. Within the proposed

new province of West Papua, Solossa drew support from the Ayamaru and

Sorong elites who had been disenchanted with Atururi when the latter was

Sorong district head. Similarly, Atururi was backed by other Bird’s

Head regional elites dissatisfied with the ethnically Ayamaru district

head. As Governor of Papua province, Solossa opposed any partition of

the province, whilst Atururi saw the creation of West Papua province as a

political opportunity.38

|

West Papua province, carved out of Papua province in 2003

|

Ethnic tensions and competition for resources also shaped the actual

composition of West Papua province. For example, new districts such as

Raja Ampat and Fak-Fak initially preferred to remain within the rump

Papua province since they feared domination by politically savvy Sorong

and Ayamaru elites.39 West Papua’s creation also resulted in

the founding of 28 new regencies, among them Teluk Bintuni that hosts

the Tangguh liquefied natural gas (LNG) processing plant operated by

multi-national BP. Project development began in 1999, and the plant

finally started shipping LNG to China, South Korea and the United States

in 2009. This US$5 billion scheme gave greater impetus to the creation

of West Papua province, which is also home to substantial logging

interests around Sorong.

Regional ethnic rivalries over the capture of resource revenues were

also visible in the proposed establishment of Central Irian Jaya

(Central Papua) province, which was supported by elements in the central

highlands and the southern coastal plain who feared domination by the

northern coastal elite. Given that this province would contain the

Freeport mining operations near Timika, the biggest gold mine and second

biggest copper mine in the world, the potential rewards were very high.

Clemens Tinal, Timika district head, and Andreas Anggaibak, Speaker of

the Regional House of Representatives, lobbied vigourously for its

creation, apparently receiving support from Indonesia’s State

Intelligence Agency.40 Opposition to the establishment of

Central Irian Jaya province came from the Amungme and other Timika

ethnic groups, and was closely linked to existing inter-ethnic disputes

among communities surrounding the Freeport mine over access to Freeport

community support funds and community leaders’ ties to the Indonesian

military. When Anggaibak formally announced the province’s creation in

late August 2003 riots ensued in which five people were killed and

dozens injured.

The rioting over the proposed establishment of Central Irian Jaya

province prompted elites from Biak and Nabire to argue that their

regions would be a safer choice to site the new province’s capital.41 This

laid bare tensions between northern coastal elites and highlanders over

access to revenues from the Freeport mine. Indeed, Timmer (2007)

suggests that, “Highlanders and people from the south-coastal regions

(Mimika, Merauke) are often consumed with envy about the power enjoyed

by northern coastal elites who have a remarkable acquaintance with

Indonesian ways of doing politics”.42 Whilst the local

population enjoys greater representation in district governments of the

highlands and the southern coastal plain, among Papuans in the

provincial bureaucracy those from northern coastal communities in Biak,

Yapen, Sentani, Sorong and Ayamaru do indeed predominate. The

comparatively low level of development across most of the highlands

exacerbates such ill feeling, and presently most violent resistance to

the Indonesian state is incubated in the highlands region. As a result,

highlanders are known to characterise northern coastal Papuans as

collaborators with the Indonesian authorities. This could yet

affect political stability in the territory since the proposal to create

Central Papua province is now back on the agenda, comprising 14

regencies with Biak as the capital and Dick Henk Wabiser, a retired

admiral from Biak as the acting governor.43

Indeed, district heads in several regions across West Papua have

pushed for their districts to become the capitals of new provinces under

pemekaran and decentralisation.44 They include

Merauke, Yapen Waropen, Serui, Biak, Nabire, Fak-Fak and the highlands

as the creation of new provinces promises access to power and resources

to regional Papuan elites. For instance, Merauke politicians have

campaigned for a South Papua province since Merauke is home to West

Papua’s largest concentration of Catholics and whose leaders have long

felt excluded by the largely Protestant and migrant dominated provincial

capital Jayapura. This proposed new province has also been home to

locally significant tribal rivalries since Merauke was divided into four

districts in 2002.45

Whilst the Papuan spring of 1999-2000 seemed to indicate that over

thirty years of Indonesian rule had inculcated a genuine pan-Papuan

national identity, in contrast to neighbouring PNG, “local support for

partition demonstrates that Papuan unity is fragile and the development

of a coherent territory wide identity remains a work in progress”.46 The

division of the territory polarised the Papuan elite between those such

as former Governor Solossa, prominent Papuan intellectuals and many

civil society groups who opposed it and other elites who stood to

benefit from the founding of new provinces, regencies and districts.

Complicating matters, the security forces have also supported the

creation of new administrative units since their establishment has

frequently been accompanied by the creation of new military and police

commands. Whilst all provincial governors under Indonesian rule have

been indigenous Papuans, they have had to tread carefully with the

Indonesian military, which has been the single most powerful state actor

since the Indonesian takeover. Greater Papuan participation in the

public sector has also seemingly destabilised the territory, with the

elections for district government heads, in particular, becoming an

arena for political conflict. So widespread has this trend become that

one analyst was moved to state, “ethnic differences play a significant

and sometimes alarming role in land and resource politics”.47 Just

as in other Melanesian states, these rivalries are playing an

increasingly visible role in West Papuan politics, not just between

different indigenous groups but also between Papuans and Indonesian

settlers. These developments indicate that corruption and political

instability would be a further challenge for an independent West Papua

authority to overcome.

Poor Government Services

The nexus of corruption, ethnic rivalries and chronic political

instability, characterised by frequent parliamentary votes of no

confidence, greatly undermines Melanesian governments’ capacity to

effectively deliver public services. In PNG, resource revenues and

international assistance have not translated into better roads, schools

and health services. Despite receiving billions of dollars of Australian

aid, scant development has occurred and per capita incomes have barely

improved since independence in 1975. Particularly during the monsoon

season, impassable roads hamper local trade and fuel internal migration

into cities and towns. Moreover, evidence suggests that public service

delivery is more problematic in multiethnic democracies.48

Likewise, West Papua is already suffering from the poor delivery of

public services, especially in rural areas where indigenous Papuans

predominate, and evidence from its neighbours indicate the delivery of

public services would be unlikely to improve after independence. Over

the last decade, the indigenous Papuan middle class has benefitted from

an expanding civil bureaucracy and increased local government funding

under decentralisation and Special Autonomy. However, it is obvious that

this newly empowered and enlarged Papuan bureaucracy has little ability

to dispense public services. Since educational standards have long

lagged behind those in the rest of Indonesia, there is a dearth of

sufficiently qualified people and many of these bureaucrats apparently

have little relevant education or experience. Indeed, it has even been

claimed that primary school teachers without administrative experience

are running agriculture departments.49 At the very least, this illustrates that Papuans badly need better education services.

"Special Autonomy has failed: Papuans’ right to life is threatened" |

Those in West Papua who advocate the creation of new administrations

argue that it improves public services in hitherto isolated rural areas

but there is little evidence that this has actually happened. Instead, pemekaran

devours much of the territory’s development budget to pay for office

construction and the hiring of the extra staff, with the result that

West Papua has the highest per capita expenditure on civil service in

Indonesia but with little indciation that performance has improved.

Indeed, in 2005 the World Bank found that in parts of Papua province the

amount spent per capita on civil servant salaries was 60% above the

Indonesian national average.50 Whilst more Papuans have

secured jobs in the civil service, their lack of education and training

has also resulted in the recruitment of more Indonesian settlers to

shore up the administration of the expanded civil service. The

territory’s poor relative performance was underlined in Indonesia’s

Regional Economic Governance Index, which surveyed 245 regencies and

municipalities across 19 of Indonesia’s 33 provinces in 2011. Districts

and cities in West Papua and Maluku comprised nine of the 10 worst

ranking units in the survey, with Waropen regency in Papua province

rated the worst of all.51 Interestingly, in a list dominated

by districts in Java and Sumatra, Sorong in West Papua province was

rated fifth best in the Index.

One of the reasons for the poor performance among indigenous Papuan

civil servants is that West Papua has long had the lowest per capita

expenditure on education in the country. This is despite it having the

highest per-capita revenue of all six Indonesian regions thanks to its

resource earnings and small population.52 In 2006 it was

reported that West Papua also had the worst participation rates in

education, with enrolment for primary education at 85%, dropping to 48%

for secondary school and 31% for high school.53 Furthermore, some 56% of the population had less than primary education and 25% remained illiterate.54 These

figures cover both migrants and indigenous Papuans across both

provinces, and are exacerbated by an unequal distribution of educational

resources, concentrated in the coastal towns and cities at the expense

of rural areas. Indeed, figures from 2005 indicate that the average

distance to junior secondary schools in densely populated Java was 1.9

kilometres whilst in West Papua it was 16.6 kilometres.55 Government

data from 2008 indicated that only 17.63% children in rural Yahukimo

district had completed their primary education. Moreover, even

indigenous urban residents are still twice as likely as migrants to have

little or no formal schooling, a disparity that was first recorded in

the 1970s.56 Newer figures from the UN Children’s Fund

(UNICEF) suggest that secondary school enrolment in Papua province is

only 60% compared to the Indonesian national average of 91%. Where

schools do exist, often there is a serious lack of books and teachers,

especially in rural areas of the central highlands since most teachers

prefer to live in urban areas.

Health indicators also paint a vivid picture of indigenous Papuan

deprivation. In 2004 West Papua had the lowest per capita expenditure on

public health in the country, despite its resource earnings.57 As

a consequence, indigenous Papuans also suffer the lowest health

standards of any Indonesian citizens. In results published in December

2010, Pegunungan Bintang district in Papua province placed last in the

Ministry of Health’s Community Health Development Index, which measures

health care across all 440 districts and municipalities in Indonesia.

Indeed, of the lowest 20 districts across the country 14 are found in

eastern Indonesia, mostly in Papua province. The quality of these health

care rankings are based on 24 indicators such as the per capita ratio

of doctors, immunisation rates, access to clean water and the incidence

of mental health problems.58 Geographic inaccessibility is undoubtedly a factor in such discrepancies, however.

As with education, health services in rural areas remain very poor,

with only a minimal government presence outside of areas with military

bases. Whilst health centres have been established in all sub-regencies,

these clinics remain poorly staffed and equipped. For instance, in 2006

it was reported that in Papua province the average distance of a

household to the nearest public health clinic was 32 kilometers, whereas

in Java it was 4 kilometers.59 In 2009 there were only 12

government hospitals, six private hospitals and 213 clinics across the

whole territory. Such inadequate primary health care affects life

expectancy, already the lowest in Indonesia. West Papua also has highest

HIV/AIDS rates in the country. The UNDP Report for 2010 notes that the

territory has the highest per capita rate of HIV/AIDS infection in

Indonesia at 2.4%, well above the national average of 0.2%, with aid

agencies critical of the government’s lack of response. Malaria and

tuberculosis rates exceed national figures also.

As a result of poor government performance in education, health and

welfare, West Papua also continues to post the lowest human development

index (HDI) scores in Indonesia, along with the country’s widest

variation in district HDIs.60For instance, in 2004 the

central highland regency of Jayawijaya had Indonesia’s lowest HDI

classification of 47, whilst the multi-ethnic port city of Sorong scored

73. In 2009 the new district of Nduga in the deprived central highlands

scored 47.45, compared to 74.56 in Jayapura, the territory’s biggest

city. The HDI also assesses how economic growth in GDP (gross domestic

product) translates into improvements in human development by comparing

average per capita GDP in each province with its HDI ranking. In 2004

Papua province scored worse than any other Indonesian province since it

ranked third in terms of GDRP (gross domestic regional product) but only

29th (out of 30 total provinces at the time) in HDI. Newer

data compiled by Statistics Indonesia in 2009 produced a similar

outcome, and ranked Papua province as 33rd out of 33 provinces and West Papua province 30th.61 Whilst

it can be argued that much of this disparity is due to the Dutch

colonial legacy and the difficulties in delivering basic services in

remote areas, the UNDP concluded that these figures are “a clear

indication that the income from Papua’s natural resources has not been

invested sufficiently in services for the people”.62

Given the wide cleavage between the migrant-dominated coastal urban

areas and the deprived, overwhelmingly indigenous interior, such

disparities in human development become even more marked. The UNDP

definition of poverty uses factors such as illiteracy, access to health

services and safe water, underweight children and the likelihood of

people not reaching 40. Under this definition, the HDI research found

that within Papua province some 95% of all poor households resided in

rural areas, markedly worse than the national average of 69% and a clear

indicator that poverty was concentrated in the indigenous population.

The UNDP also found that only 40% of poor households had in excess of

five family members, again under the Indonesian average, which reflected

higher than average infant mortality rates.63 Indeed, among

children aged under five and classified as poverty stricken, over 60%

were malnourished, as opposed to only 24% of poor children in the

Java/Bali region.64 Of these poor households in West Papua,

some 69% lacked access to safe water, 90% suffered inadequate sanitation

at home and over 80% had no electricity. Half of all poor households in

the territory lived in villages accessible only by dirt road, hampering

the rural poor’s access to markets. At the same time, some 90% of poor

households lived in villages with no telephone, 84% lived in villages

without a secondary school and 83.5% lacked access to bank or credit

facilities.65

|

Papuan children in the rural highlands, Papua province

|

Whilst both provinces in the territory continue to post HDI outcomes

well below the Indonesian national average, their scores since 1999 have

shown an upward trend, although how much of this is the product of

rising rates of in-migration is difficult to quantify. For instance,

Papua province’s HDI rose from 58.80 in 1999 to 64.53 in 2009, whilst

that of West Papua province was 63.7 in 2004 and 68.58 by 2009. By

contrast, the Indonesian national average was 64.3 in 1999, and had

risen to 71.76 in 2009.66 Over the border in PNG, HDI figures

have been consistently lower than those of West Papua with worse

results in all the key indicators of life expectancy, literacy and per

capita GDP. Nevertheless, the existence of large rural to urban

variations and high numbers of migrants in West Papua make any direct

comparisons between the indigenous populations of PNG and West Papua

difficult.

In the poor delivery of government services West Papua already shares

much in common with its neighbours, particularly PNG and the Solomon

Islands. Prior to Australian intervention in mid-2003, the central

government in Honiara had lost control of the country and services had

largely collapsed. Many civil servants had simply stopped turning up to

work, whilst those who did often received no salary. Treasury officials

and government ministers were also frequently intimidated at gunpoint.

Whilst the situation in PNG has never plumbed such depths, tribal

fighting in the past two decades has exacted a heavy toll on public

service delivery, especially in Southern Highlands, Enga, Western

Highlands and Simbu Provinces. In these populous regions the destruction

of schools, medical facilities and other government infrastructure has

seriously disrupted development in the affected areas, forcing teachers,

health workers, and other public servants to flee to safety. Even in

regions not prone to inter-group violence, public service had been

widely perceived as inadequate, and even the World Bank and the

International Monetary Fund (IMF) have voiced concern over poor service

delivery. As in West Papua, the civil service is seen as eating up most

of PNG’s national budget in salaries and benefits but with precious few

results to justify its existence.67 Delivering sufficient

healthcare, education and basic infrastructure will be probably the

biggest challenge for an independent West Papua given the present

realities and difficult terrain in the remote interior. Nevertheless,

the resource revenues that the territory enjoys should make it possible

to better tackle these issues, if civil service performance can be

improved.

Dysfunctional Economies

The Asian Development Bank noted in 2010 that, “PNG, Solomon Islands,

and Timor-Leste are finding it difficult to diversify and stimulate

growth beyond exploitation of nonrenewable oil, minerals, and forests.”68 As

with West Papua, these economies remain heavily reliant on resource

revenues, being hampered by low productivity in agriculture and an

almost non-existent manufacturing base. Even tourism, which could

provide a much-needed boost to the service sector of these economies, is

held back by the fragile security situation in West Papua and its

neighbours. Furthermore, the characteristics of resource dependence

create distortions that increase vulnerability to external shocks, such

as a collapse in commodities prices, and promote inequalities between

internal regions and ethnic groups.

The enclave nature of mining and fossil fuel extraction in particular

exacerbates the large imbalances in West Papua’s economy and ensures

the benefits are not distributed equitably. Indeed, much of these

windfall gains are highly concentrated in a few regions to the detriment

of the rest of the territory.69 Moreover, due to the

territory’s historically low education budget, relatively few Papuans

secure skilled jobs in major projects like BP’s LNG processing plant or

Freeport’s gold and copper mine. Thus, despite its resource wealth, West

Papua suffers from Indonesia’s highest poverty levels. Government data

from 2010 indicated that around 35% of the territory’s population still

lived below the poverty line, compared to the national average of around

13%, with income disparities also the widest among Indonesia’s six

regions. In 2002 a mere 34% had access to clean water and 28% to

adequate sanitation, whilst just 46% were on the electricity grid, the

lowest level in all of Indonesia.70 In 2005 Indonesia’s

Ministry for the Development of Disadvantaged Regions classified 19 of

20 regencies across Papua province as underdeveloped.

A large underground economy is another feature of a failing state,

and in both PNG and West Papua the growing Asian presence in resource

extraction, hotels and other commercial enterprises has resulted in

rising levels of corruption and organised crime.71

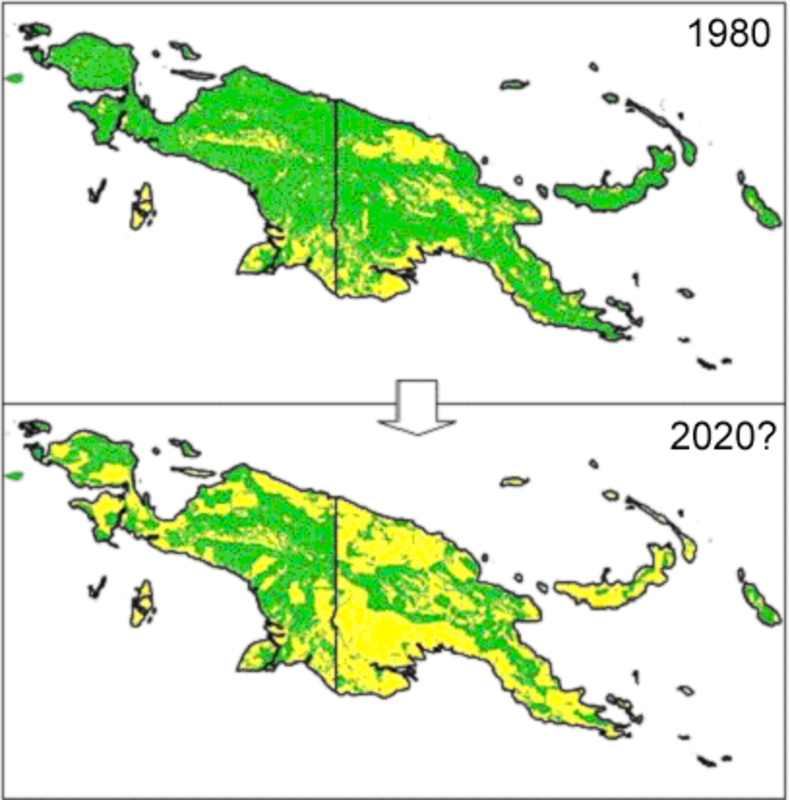

Illegal logging is particularly lucrative since New Guinea is home to

the world’s third largest tropical forest, surpassed only by the Amazon

and Congo Basins. As such, it is home to the last undisturbed

large-scale forest in the Asia-Pacific, and as commercial timber stocks

in Sumatra and Borneo are increasingly depleted the Indonesian and

Malaysian logging industry has turned its attention towards West Papua

and PNG. A senior official at Indonesia’s Ministry of Forestry conceded

in 2010 that around 25% of West Papua’s forests have fallen to legal and

illegal loggers since the late 1990s, with the forested area falling

from 32 million hectares to 23 million hectares.72 In PNG it

is widely estimated that some 70-90% of all the country’s logging is

illegal, much of it due to the Malaysian firms that dominate the

country’s timber industry.

Most logging operations in West Papua, PNG and the Solomon Islands

are socially, environmentally and economically unsustainable since land

custody is central to the survival of indigenous rural communities.

Logging often damages the self-sufficiency of such communities since

their opportunities to grow food, to hunt and to catch fish are reduced.

Drinking water sources and materials to build houses are also lost or

degraded. Given that government-led development is conspicuous

by its absence in many rural areas, local communities are vulnerable to

logging company promises of roads, schools, health clinics, and

revenues. Aside from arterial roads to transport logs, most of these

promises usually go unfulfilled. Instead, spoiled land and polluted

water are the most visible legacy of logging operations across

Melanesia.

Special Autonomy has added to the regulatory confusion in West Papua

as swathes of overlapping and contradictory regulations issued at the

national level, provincial level and district level have facilitated the

increase of both legal and illegal logging. Local timber elites take

advantage of the many loopholes to secure many small-scale licenses,

ostensibly to benefit local residents but in actuality for the profit of

timber firms. These elites can include Papuan community leaders,

politicians, civil servants, military and police officers. These same

local elites are also thought to be responsible for the increase in

illegal logging in West Papua province, often in collusion with

Malaysian, Korean and Chinese logging companies now present in the

territory. China, having already reduced its own logging due to

environmental concerns, is the biggest market for Papuan timber.73 Indonesia’s

Ministry of Forestry estimated in 2004 that over seven million cubic

metres of timber were being smuggled out of West Papua annually,

equivalent to 70% of the total volume of timber leaving Indonesia

illegally each year.74 The situation in West Papua is thus

reminiscent of a pattern that has been repeated across Melanesia

whereby, “Assignment of the right to sign logging contracts to tribal

chiefs or ‘big men’ has led to a situation where rights to harvest are

granted by landowners in return for a pittance, in terms of their share

of the revenue in excess of logging costs”75 Indeed,

corruption in the logging industry has become embedded in

post-independence Melanesian politics as it provides significant

revenues for local leaders to distribute to their supporters.

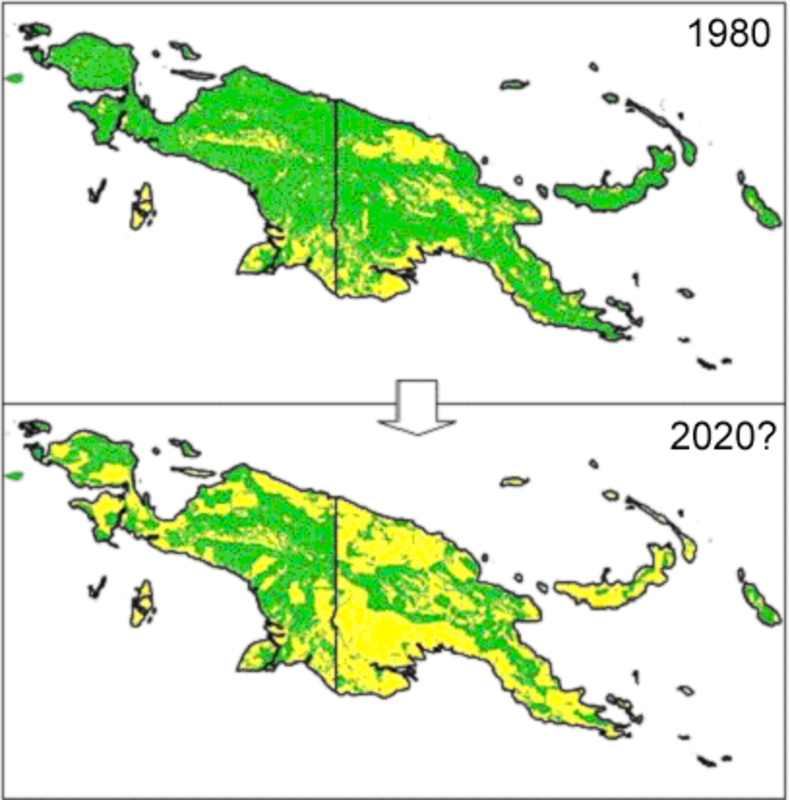

Deforestation across both sides of New Guinea

|

The Indonesian security forces are also heavily involved in legal and

illegal logging in West Papua, and it is a particularly lucrative

sideline since even the lowest ranks can earn money from it. The

military and police are often employed by logging firms to deal with

local communities angered by displacement from their customary lands and

environmental damage. Wasior in West Papua province has been the scene

of particularly violent conflicts between timber companies and locals

protesting the lack of compensation, which has resulted in retaliatory

action by elite police paramilitary brigades that forced around 5,000

locals from their homes.76 Moreover, several forestry

concessions are part owned by military foundations, and leaked US

Embassy cables reveal the private concerns of American officials over

the military’s role in West Papua. An October 2007 US Embassy cable

quoting an Indonesian foreign affairs official stated that, “The

Indonesian military (TNI) has far more troops in Papua than it is

willing to admit to, chiefly to protect and facilitate TNI’s interests

in illegal logging operations.” An earlier cable from 2006 cites a PNG

government official as saying that the TNI is “involved in both illegal

logging and drug smuggling in PNG.”77 Indeed, the removal of

the Indonesian military from West Papua would constitute a major

improvement in the lives of most indigenous Papuans.

The need for foreign exchange has also ensured that logging in the

Solomon Islands has greatly exceeded sustainable levels in most years

since 1981, and began with collusion between Malaysian logging firms and

individual government ministers. At present logging composes around 70

to 80% of the country’s exports by value but recent estimates suggest

that forestry reserves will be depleted by 2014.78 The

inevitable collapse of the logging industry in the Solomon Islands could

likely result in an economic shock to the fragile state and might even

lead to another uprising, as in the late 1990s. As such, logging is a

major source of political instability in the Solomon Islands, and

similar tensions are visible in West Papua too, with many local

communities resentful of logging firms and their Indonesian settler

staff.

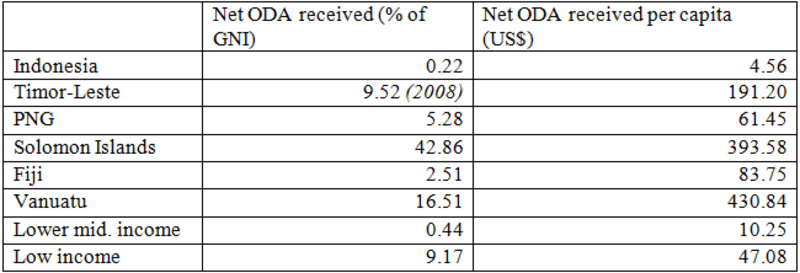

Addiction to foreign aid is another characteristic of a dysfunctional

economy, and many of West Papua’s neighbours exhibit symptoms. For

example, in recent years foreign aid has constituted over 60% of the

Solomon Islands’ development budget, and it was one of the world’s top

three aid dependent countries between 2005 and 2007.79 Foreign

aid to the country in 2007 made up some 47.1% of gross national income

(GNI), much higher than the low income country average of 7.7%, although

this figure was inflated by the large Australian presence attempting to

reform the country’s law and order institutions. Whilst the disparity

between the Solomons and other low income countries in aid dependency

had reduced somewhat by 2009, the latest year for which data is

available, the figures below indicate only a marginal improvement.

Likewise, PNG and Vanuatu, both classified as lower middle-income

countries by the World Bank in 2011, each receive proportionally much

more foreign aid than the average for lower middle-income economies, as

does Fiji, which was recently upgraded to upper middle-income status.

Despite its oil and gas revenues, Timor-Leste also remains heavily reliant on foreign assistance to feed its population.

Regional Aid Dependence in 200980

Aid has also been compared to the resource curse whereby large

revenue inflows encourage political rent seekers and retard development

outcomes, a fact recognised by the Asian Development Bank (ABD) in its

attempts to promote policy reform in the Pacific.81 The ABD

acknowledges its biggest challenge has been how to overcome a paucity of

political will for reform in the recipient country, the lack of which

severely limits the impact of aid. Aid also offers legitimacy to corrupt

and incompetent regimes, enabling them to cling to power even when they

have lost popular support. Employing empirical data from some 108

recipient countries over a 40 year period, another study argues that,

“since most foreign aid is not contingent on the democratic level of the

recipient countries, there is no incentive for governments to keep a

good level of checks and balances in place”.82 These findings

suggest that foreign aid weakens democratic rules and corrupts

political institutions in recipient countries. This does not bode well

for the consolidation of democratic institutions in an independent West

Papua since it is likely the nascent state would also be reliant on

various forms of development assistance, at least in the short to medium

term.

Aid agencies would undoubtedly play a role in any emerging Papuan

state and a critical issue would be land ownership. In Timor-Leste

international agencies such as AusAID (Australia’s overseas aid

programme), USAID (United States Agency for International Development)

and the World Bank have been strongly advocating land commercialisation

through robust titles and registration. Anderson (2010) notes that

AusAID has also been the most vocal agency encouraging land reform in

Melanesia where it has strongly promoted the Australian land title

model. However, he argues that in many former colonies such

commercialisation of customary lands has frequently displaced

communities from their land and damaged local food security and

distribution networks.83 The vast majority of land in

Melanesia, and to a lesser extent Timor-Leste, is still held under

customary laws, not officially registered or even written down. This is

because at independence most Melanesian constitutions enshrined

customary land holding systems and little of this land has been sold or

leased as yet. On the other hand, powerful regional actors such as

Australia and the United States argue that the commercialisation of

customary land through central registration increases agricultural

productivity and spurs economic development. Melanesian notions of

customary land have also been under siege from loggers, miners and other

investors, in addition to corrupt local and national interests. Citing

the case of post-colonial Kenya however, Anderson suggests that central

land registration may actually fuel land disputes, instead of securing

tenure as its proponents argue, since elites often claim more land that

they have rights to under customary laws.84 As in West Papua,

commercialisation can also disadvantage uneducated or powerless rural

communities since they are vulnerable to fraud and deception in which

their traditional lands can end up registered to someone else. Even in

fully transparent registration cases, secondary traditional owners such

as wives and sisters frequently do not get listed in the land register.

Proponents claim there are numerous advantages to customary land

tenure such as widespread employment, ecological management, cultural

maintenance, social cohesion and local food security.85 However,

rapid population growth in West Papua and across Melanesia means that

whilst subsistence production remains essential for rural communities,

current methods of production are not enough to satisfy contemporary

national requirements. Whilst it is possible that small farming in

Timor-Leste, West Papua and across Melanesia might be sustained it needs

better infrastructure to support local markets, to enhance rural health

and education services, and to balance the raising of export crops

alongside traditional subsistence production. However, the trend in many

parts of Indonesia since 1997 has been to pursue cash crop production

and land rationalisation, which often displaces and marginalises

small-scale agriculture.

West Papua has not been immune to these changes sweeping through

Indonesia, and almost fifty years of Indonesian rule have resulted in

parts of the territory having a very different system of land tenure

than its Melanesian counterparts. Moreover, it is highly likely that an

independent West Papua would face many of the same land title disputes

that have beset Timor-Leste since 1999 as it has transitioned from being

an Indonesian province to an independent state. A pre-existing lack of

clarity in land titles was exacerbated by Indonesian military

orchestrated violence immediately after the country’s vote for

independence, which destroyed much of the new nation’s infrastructure,

buildings, and land tenure documents. As in Timor-Leste, resolving land

conflicts bottled up by many years of Indonesian rule would also be a

major undertaking in an independent West Papua.

Breakdown of Law and Order

In the last decade Australian military and police have intervened in

the fragile states of PNG, Solomon Islands and Timor-Leste to counter a

downward spiral in law and order. For instance, the Australian presence

in the Solomon Islands has resulted in the removal of around 25% of the

Solomons police force, with a large number of those charged with

criminal offences.86 The withdrawal of Indonesia’s repressive

security apparatus would invariably leave a vacuum in an independent

West Papua, and would quite likely require the dispatch of international

peacekeepers as in Timor-Leste. A homegrown security apparatus in West

Papua would be much smaller than that of Indonesia. Developing a

competent Papuan police force would be one of the first challenges to

address since the only positive legacy of the suffocating Indonesian

security presence has been to keep a lid on some of the law and order

issues that have beset neighbouring PNG. Anecdotal evidence suggests

that guns are much easier to obtain in PNG than in West Papua and the

country is increasingly lawless. This is demonstrated by the increase of

jail breakouts in recent years, and it has long been unsafe to walk the

streets of Port Moresby and other larger towns at night. Even staff at

the country’s Bomana high security prison have aided and abetted the

escape of particularly dangerous prisoners. Much of the breakdown in law

and order has been attributed to the proliferation in illicit firearms,

resulting in escalating violent crime rates, the increased deadliness

of tribal disputes, and a worsening delivery of essential services.

“Largely as a consequence of the ready availability of small arms, Papua

New Guinea is widely identified as the tinderbox of the south-west

Pacific.”87

Indeed, the situation in parts of PNG represents a warning for any independent West Papua across the 141st

meridian east. Even though the actual number of guns in PNG is less

than in other violent societies, such illicit firearms are reportedly

two to five times more likely to be used in homicide in PNG’s Southern

Highland province than similar weapons in the other high-risk countries

such as Ecuador, Jamaica, Colombia and South Africa.88 Moreover,

the social effect of firearms in PNG, the Solomon Islands, and to a

lesser extent Fiji, can be significant, with markets suffering, school

attendance dropping, and an exodus of development agencies, health

professionals, and civil servants occurring.89 Particularly

in PNG’s Southern Highland province where the colonial regime left

relatively little trace, tribal fighting has become increasingly

widespread and increasingly deadly in the last 20 years due to an easier

availability of guns, which have replaced traditional weapons such as

bows and arrows and spears. Frequent tribal feuding has inculcated a gun

culture, which further ingrains lawlessness and even glorifies criminal

behaviour in times of inter-group fighting. Even the hiring of

mercenaries has been a feature of clan conflict in this region of PNG.

Modern weapons have thus altered the nature of conflict, and rendered

unworkable the traditional mechanism of paying compensation in pigs. The

origins of violent conflict in the highland provinces are multifaceted

and include land disputes, competition for state resources, traditional

animosities and sequences of revenge and retribution that extend back

decades. Similar factors also cause armed group violence in Timor-Leste,

which periodically surfaces in both urban and rural areas. The

breakdown in law and order across PNG, especially in the populous

highland region, is also due to greater human mobility and the upheaval

caused by large-scale resource extraction. One result is that the PNG

police have disavowed their responsibility for policing tribal warfare,

which is now seen as a ‘traditional’ activity even when deaths are

involved.

Police inaction has permitted an increase in gangsterism and criminal

activity, particularly roadblocks and robbery, which have seriously

compromised the delivery of essential public services in many highland

areas of PNG. A further contributory factor to crime and gangsterism has

been the ongoing monetisation of the local economy, along with

population growth that fuels disputes by simply placing people in

greater proximity to one other. Indeed, one of the reasons for the

increase in crime and disorder across Melanesia is demographic change. A

growing population compounded by rising numbers of unemployed youth in

urban areas results in greater crime and lawlessness, which in turn

further dissuades investment and results in a vicious circle of fewer

opportunities and rising crime. Melanesia is currently experiencing both

the highest population growth rates and the fastest urbanisation rates

in the whole Pacific.90 Even though average population growth

is some 2% per annum, the urban population growth rate is 4.7% per

annum, meaning that the region’s urban population is now doubling every

17 years as their total populations double every 30 years. Over half of

Melanesia’s population is 24 or under.

In the last decade population growth in West Papua has outstripped

that of Melanesia as whole. Whilst Indonesia’s 2010 census found that

the whole country’s population had increased at an annual rate of 1.49%

since the previous census in 2000, the annual rate of increase for Papua

province was 5.48% and for West Papua province was 3.72%. This made

them the fastest and fourth fastest growing provinces of Indonesia

respectively. The combined yearly growth rate of the two provinces was

5.09% between 2000 and 2100, meaning that since 2000 the combined

population increased 64%, more than any other province in Indonesia.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the pace of growth by 2010 had

surpassed the yearly average of 5.09%, meaning that the rate of

migration into West Papua could be continually rising.91 Given

West Papua’s relatively small population in comparison with Indonesia

as a whole, even relatively low levels of migration from other regions

can deliver dramatic demographic change. Whilst most of the population

increase is due to rising levels of Indonesian migration, the latest

census also counted the territory’s fertility rate at 2.9, higher than

the national average of 2.3. Therefore, population growth, increasing

urbanisation and a looming youth bulge constitute further challenges for

policy makers in West Papua to grapple with.

State Legitimacy

Another result of increasing lawlessness and poor governance is the

loss of state authority and legitimacy throughout much of Melanesia.

Indeed, state weakness seems ingrained throughout the region, the deep

lying reasons for which would likely be replicated in an independent

West Papua. Lacking long traditions of centralised authority, the

institutional foundation of the modern nation-state remains a somewhat

alien imposition that rests uncomfortably on these relatively new

nations. Being among the most linguistically and socially diverse in the

world, this region represents the antithesis of the imagined community.92 Consequently,

Melanesian states have never been able to impose the centralised

authority that is at the core of the modern nation-state, with central

governments often having minimal or no presence outside their capitals.

Where the nation state is visible it is often poorly regarded,

particularly in rural areas of PNG. As with Freeport in West Papua, in

many remote areas across Melanesia the church or mining companies have

replaced the government by serving as surrogate states that provide

public services and infrastructure like health, education and roads.